How accessible are your comms?

How accessible are your comms?

So, did you catch the BAFTAs in all their luvvie glory? It was largely the usual fare: outlandish gowns, embarrassing jokes, and suppressed envy. But amidst all the tears and taffeta, there was a genuinely uplifting moment – and we’re not talking Rebel Wilson’s golden bras here. For the first time a deaf actor won a BAFTA in one of the main categories.

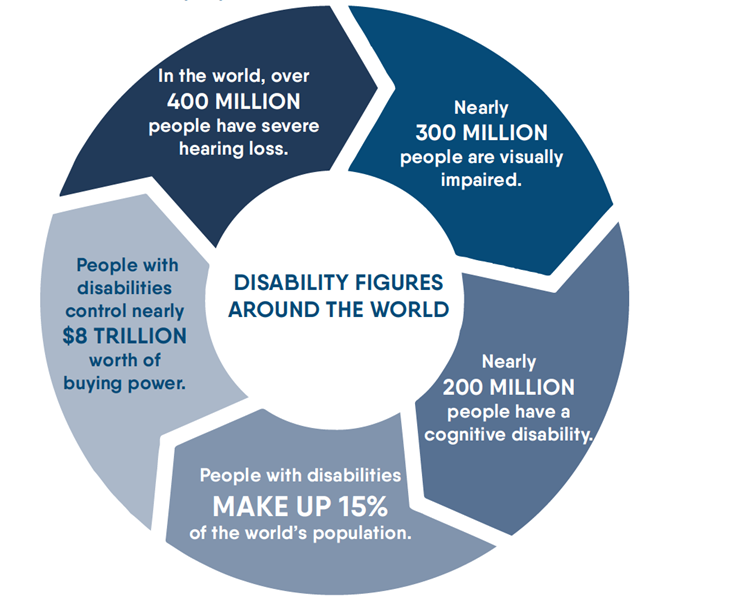

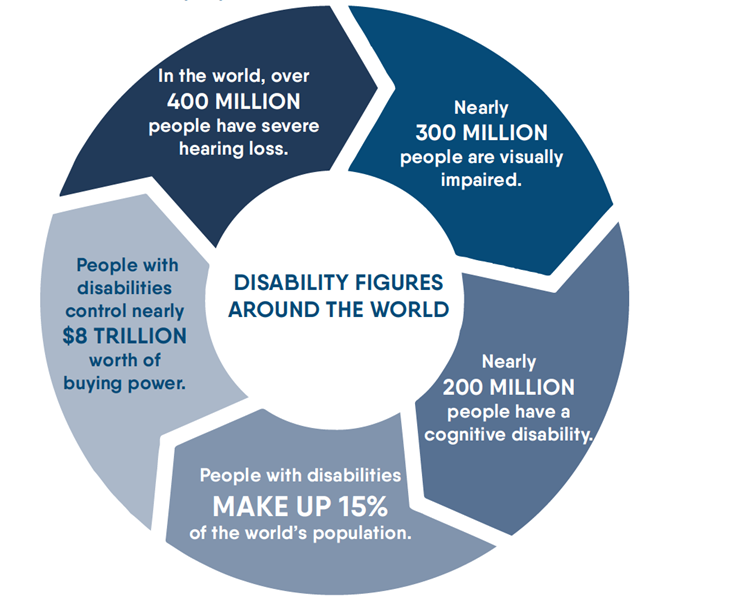

As Troy Kotsur made history for his supporting role in ‘CODA’, perhaps the one in six UK adults affected by hearing loss finally felt included. It was certainly a telling reminder that disability access and inclusion is not just about bodily access to buildings and transport. It’s about access to content too.

For Erin O’Reilly, Communications Director for Leonard Cheshire, the issue is clear: “Accessibility should not be something people have to search for. It should be standard.” Information that’s clear, direct and easy to understand benefits all audiences. But how inclusive are your comms? Can the 15% of the UK population with a disability or impairment understand and access the information you share easily? Or would they feel excluded and alienated?

Reaching a wider audience

If we want to reach as many people as possible, we need to make reasonable adjustments, adapting our usual way of communicating to remove any barriers for disabled people and those with communication difficulties.

There are four types of condition most directly affected by the accessibility of content and campaigns:

Visual – blindness, low vision and colour blindness. Colour blindness or colour vision deficiency (CVD) affects around 1 in 12 men, and 1 in 200 women.

Hearing – deafness and hard of hearing. At least 4.4 million people of working age have hearing loss, and 1 in 10 of us live with tinnitus.

Cognitive – dyslexia, autism, seizure and learning difficulties. Dyslexia is the most common of all neuro-cognitive disorders, affecting 15% of the UK population.

Speech – speech impediments, inability to speak. It’s estimated that 20% of the population will experience communication difficulty at some point in their lives.

How to be more inclusive

There are some very straightforward rules you can apply to your comms to make them easier to access and understand for everyone.

Fonts

• Avoid fancy fonts which can be difficult for people with dyslexia to read. Choose a san serif font such as Arial or Comic Sans instead.

• Align text to the left and avoid italics, underlining and writing whole words in caps.

Colours and contrast

• Font and background colour can make a big difference to readability. Ensure there’s enough contrast between the two and keep backgrounds plain rather than patterned.

• Use white text sparingly. When using black text on a white background, an off-white background is better.

• Don’t rely on colour-coding alone to convey meaning, such as green for positive actions and red for negative. People with CVD may not be able to process the difference, so make sure the text explains things clearly.

A rainbow of paint stripes colour corrected to show how it might be experienced by a person with Protanopia type colour blindness.

Where to get help: there are free professional contrast checkers online. Try the one from web accessibility organisation WebAIM.

Images and icons

• Icons and visuals are appealing and can help people who are neurodiverse, dyslexic, or who have visual impairments to process and understand your message. But be aware that screen readers announce emojis as words which can be confusing.

• If you’re using images in a digital communication, make sure you include Alt text, a separate text description of the image. This enables anyone using a screen reader to fully understand your content.

Language

The average literacy level in the UK is the same as that of a 9 to 11-year-old, so make your text as readable as possible:

• Use plain, simple language. Avoid jargon and spell out acronyms.

• Signpost clearly – headings, subheadings and bullet points all help a reader find their way through your content more easily. Break up your text with visuals.

• Use everyday examples to help explain difficult ideas.

• Keep sentences short, at around 25 words. Sentences with 40+ words will make your text harder to read.

• Use inclusive language. Try to avoid phrases that link disability with negative things, such as ‘falling on deaf ears’ or ‘blind drunk’. However, most people with impairments are comfortable with common phrases used to describe daily life. People who use wheelchairs ‘go for a walk’ and a visually impaired person can ‘see what you mean’.

Where to get help: the Hemingway App assesses the reading age of your content and identifies any sentences that are hard to read.

Content navigation

• If you’re writing for the web or email, try to keep all your content on the page rather than asking people to download material. This makes it easier for anyone with cognitive impairments.

• If you do need to include a link, rather than just using ‘click here’, tell them where the link will take them. Make sure support or help is easy to access too.

Web

If you’re creating a website or a mobile app for a public sector body then you have a legal obligation to conform to standards set out in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. You can find out more at GOV.UK

Where to get help: try free tools such as Wave and Microsoft Chrome’s free Accessibility Insights for Web extension which will run an accessibility check on your web pages.

Video and events

• If possible, make sure your message is easily understood from both the visual content and the soundtrack.

• Use subtitles for hard of hearing, and closed captions to narrate what’s happening visually for those who can’t see.

• Send out written or visual materials ahead of an event and make a recording available afterwards. This can help people to absorb information in a way that suits them best.

A few final tips

Use multiple channels – give people more than one way to access your comms whenever you can. Could you offer recordings, transcripts, or add subtitles or signing? If you’re printing a leaflet, consider creating a digital or large print format too.

Ask your audience – ask disabled people within (or outside) your organisation to review your comms and give you feedback on any accessibility issues. Why not set up an inclusion group to help develop a strategy for producing information in accessible formats? You can also ask disability organisations for advice.

Make a start today – making your comms fully accessible isn’t a quick fix. It’s an ongoing, continual process that takes time. Why not start with your internal comms? Improving communication could help you build a more engaged workforce with a greater understanding of your business.

This isn’t intended as a comprehensive guide, but we hope it will help you get started.

The good news is that by making your comms more accessible you can be confident that you’ll reach as wide an audience as possible and be better understood. It’s good at a human level and good for business.

To revisit the BAFTAs for a moment, in an interesting counterpoint to Kotsur’s award, Mark Mangini, winner of the BAFTA for Sound, suggested: “Next weekend, don’t just go see a movie, go hear a movie.” By thinking about alternative ways to share our message, perhaps we can all become better communicators.

Recent posts

-

23rd May 2024

From equality to equity – the changing face of EDI -

22nd June 2023

Why go looking for your inner child? -

8th June 2023

Why employer-supported volunteering does everyone good